Op-Ed: Black Birthing People and Babies are Dying at Higher Rates

Black mothers and babies die at a higher rate than other Americans, data show. (Photo by pixelheadphoto digitalskillet via Shutterstock)

/

Black babies are dying at three times the rate of other babies in their first year of life.

Black pregnant people are three to four times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes than other Americans.

Dying.

Let these two stark facts sit for a minute. Often these statistics are assumed to be a function of poverty and access to care, but the unequal death hold true across income and education levels. The research is clear: the stress of experiencing racism, discrimination in care and other unjust social drivers of health are root causes of this gap.

If Covid-19 has taught us anything during the last year, it is that we must confront the fact that our communities of color have disproportionately shouldered the pain—and burden—of the inequities that exist across our systems.

Last week, the Board of Supervisors proclaimed the week of April 11 to 17 as Black Maternal Health Week in Santa Clara County to raise awareness of the tragic outcomes experienced by birthing people of African Ancestry across this Country and locally in our own County.

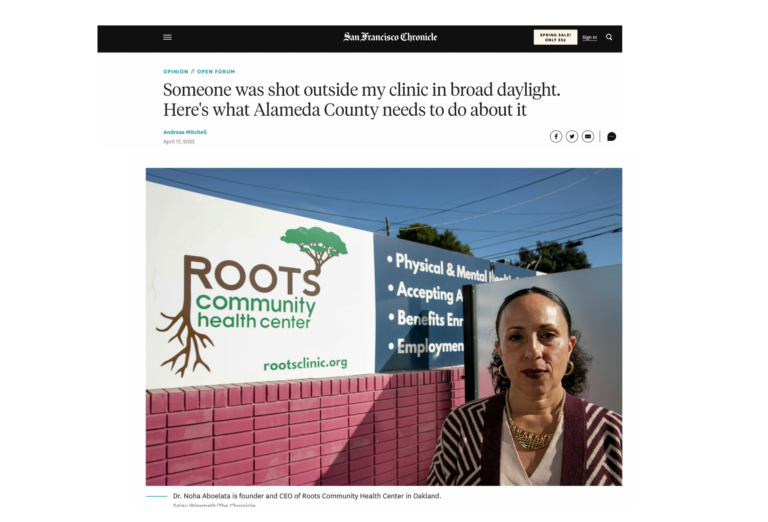

Here in Santa Clara County, our Black Infant Health Program has been working since 1991 to address these issues to support Black pregnant birthing people and their infants. Partnerships with the Roots Community Health, the African American Community Services Agency, the Black Leadership Kitchen cabinet and others provide valuable services and supports to African Ancestry families to improve health.

So the problems are being addressed, but there is so much more to do. There is still little public knowledge of our nation’s Black Maternal Health Crisis—which is why marking this week is so important.

The good news is that scientists and journalists are bringing these facts to the forefront, thus allowing policy makers, community-based organizations, clinics, concerned citizens, and advocates opportunities to work toward improving birth outcomes for our parents and babies. It is possible: history tells us that there was a brief time when the infant mortality disparity along racial lines was almost negligible.

According to a 1989 journal article by Kenneth Chay and Michael Greenstone, the brief period between 1965 and 1970 was the only time in the U.S. that the infant mortality rate for Black babies declined sharply and stabilized nearly on par with White babies. During that time frame, death among black infants in their first year of life fell by 30%. The infant mortality rate for black babies held at 2.8 per 100 births and the ratio between black and white infant mortality was 1.6.

Experts say that infant mortality is an important indicator of a community’s overall physical health. That being said, between 1965 and 1970 was the healthiest time in U.S. history for people of African ancestry and today the indications are that the overall health of our African ancestry community is very poor.

The period between 1965 and 1970 was one of unique activism in our history demanding change and confronting racism. We should embrace the lessons of that period – both that dramatic improvement is possible, and that activism and confronting racism are essential. We all must do our part to advocate for change, educate ourselves on the connections between racism and health, and take tangible steps to improve outcomes.

As a member of the Board of Supervisors, I have committed to listening to experts and those with lived experience in this area of health services and to taking action on their recommendations. One key issue is building awareness of this dramatic disparity, not just among the African ancestry community that lives this story, but among healthcare providers, family serving agencies and community allies. But after awareness must come action.

We must commit to expanding and resourcing the supports that are provided to pregnant and parenting families through programs like Black Infant Health, Roots’ Families First, and other programs that support wellness, community and advocacy for African Ancestry families. We must support legislative changes at the federal, state and local levels like the Black Maternal Momnibus Act of 2021 that address systemic issues in our pregnancy and labor and delivery services through funding, data, workforce development and accountability.

And as one of those partners, Roots clinic will work alongside Supervisor Ellenberg and the entire Board of Supervisors to identify and implement solutions to alleviate and then eliminate this injustice here in Santa Clara County. It was done once before; we must demand that outcome again.

You can help in this work, too. Join us. Support our work. And bring others along with you.

Solutions to this problem demand fortitude, determination and focus—to all of which we commit without hesitation.

Susan Ellenberg is the Santa Clara County District 4 supervisor. Alma Burrell is the regional director for the South Bay at Roots Community Health. Opinions are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of San Jose Inside. Send op-ed pitches to [email protected].